-

Steve Jackson

Survey of Communication Theory:

Spiral of Silence

- Home -

(Note: This paper was written at the University of South Carolina)

by: Jill Martin, Karin Peters

27 September 1999

In 1980, German journalist Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann published a book that sparked both controversy and a flurry of studies in the mass communications arena. The book explained her communications theory "The Spiral of Silence." Although it has been refuted more than once, her theory is nonetheless a compelling one.

According to the spiral of silence theory, people who believe that their view is widely supported will speak out self-confidently, while those with a different view will stay quiet and withdraw. As more people are encouraged either to express their views openly or to remain silent, one view becomes dominant, while the other disappears from public view entirely. Motivated by fear of isolation, the people who fall silent wish to at least appear to share the seemingly universal dominant view. Noelle-Neumann's Allenbach Institute tested this theory, beginning in January 1971, using a series of questionnaires presented in interviews to various groups of people. The first aspect of the theory that she tested was the concept that people can actually detect the climate of public opinion in order to express their views or not accordingly ( Noelle-Neumann, 1980). Her first series of questions asked

- If you had to make the decision, would you say that the Federal Republic should recognize the DDR (East Germany) as a second German state, or should the Federal Republic not recognize it?

Now, regardless for the moment of your own opinion, what do you think: are most of the people in the Federal Republic for or against recognizing the DDR?

What do you think will happen in the future: what will people's views be like in a year's time? Will more people or fewer people favor the recognition of the DDR then than favor it now? (Noelle-Neumann, 1980)

Surprisingly, 80-90% of the people interviewed readily gave their assessment of what everyone else thought, and a full 60% gave their predictions for people's opinions in the future, rather than asking "How should I know?" Further interviews with different sets of questions consistently showed an ability of the people to sense both majority and minority opinion with absolutely no published poll figures. In December 1974, Noelle-Neumann set out to systematically test the accuracy of these perceptions. During that year's election between the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats, she found that small changes in the general orientation of the public correlated with swings in actual voting intention (see Figure 1). Further similar tests in the next 5 years supported the hypothesis that the public can in fact perceive public opinion fairly accurately (Noelle-Neumann, 1980).

Noelle-Neumann, 1980

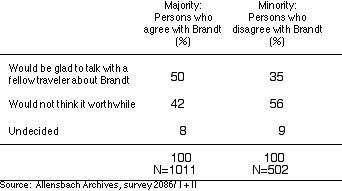

Figure 1Another major test that Noelle-Neumann conducted was the train test. In this case, she was attempting to explain the distortions that sometimes occur in the correlation between actual public opinion and perceived public opinion by hypothesizing that different camps vary in their willingness to openly expose their views in public, where their signals can be seen. The Allensbach Institute first conducted the train test in January 1972, in an interview with housewives on the issue of raising children. The housewives were presented with a sketch showing two housewives, each with a different view on spanking. One of the women is saying, "It is basically wrong to spank a child. You can raise any child without spanking." The other says, "Spanking is part of bringing up children and never yet did a child harm." Forty percent of the women interviewed agreed with the first woman, 13% with the second. They were next presented with the following situation: "Suppose you are faced with a five-hour train ride, and there is a woman sitting in your compartment who thinks [the view opposite the interviewee's]. Would you like to talk with this woman so as to get to know her point of view better, or wouldn't you think it worth your while?" Thus, all the housewives interviewed were faced with someone with an entirely different view from their own. The Institute repeated the train test with different groups of people and different questions. It found that those holding the majority opinion were more likely to be willing to discuss it with the fellow passenger (see Figure 2), supporting Noelle-Neumann's hypothesis (Noelle-Neumann, 1980).

Noelle-Neumann, 1980

Noelle-Neumann, 1980

Figure 2Public opinion plays a prominant role in Noelle-Neumann's theory. Much of spiral of silence depends on the assumption that people are motivated by fear of isolation when they go against public opinion. In The Social Contract, Jean-Jacques Rousseau states:

- Each individual, as a man, may have a particular will contrary or dissimilar to the general will which he has as a citizen. His particular interest may speak to him quite differently from the common interest. . .In order then that the social compact may not be an empty formula, it tacitly includes the undertaking, which alone can give force to the rest, that whoever refuses to obey the general will shall be compelled to do so by the whole body.(1950)

According to Rousseau, not going along with the will of the public is a major offense. Thus, in order to avoid alienation, many people will keep their contrary opinions to themselves. This silencing of weaker opinions also has implications in the area of public policy. Supposedly, public policy is based on public opinion. But since there is no one "mass public opinion," the question arises of exactly whose opinion is represented during policymaking. Dreyer and Rosenbaum address this issue in their book Political Opinions and Electoral Behavior: "If opinion is to affect policy, it must make its way through the political system to decision makers, and the system does not give equal weight to all opinion" (1966). Certain parts of society are better able to make their opinions known and thus have greater influence over public policy. Consequently, the news media, a prominent source of information about public opinion and possibly even a surrogate for it, is quite powerful (Kennamer 1992). In fact, "in every survey where people are asked, who in today's society has too much power, the mass media are ranked right there at the top" (Noelle-Neumann, 1980). In The Spiral of Silence, Noelle-Neumann devotes the chapter "Public Opinion Has Two Sources" to discussing the role of the media in influencing public opinion: "The two sources we have for obtaining information about the distribution of opinions in our environment [are] firsthand observation of reality and observation of reality through the eyes of the media" (Noelle-Neumann, 1980). She found that those exposed to more television would sometimes detect a change in public opinion where others would not. Because journalists' views are guided by their convictions, and their convictions differ generally from those of the rest of the public, journalists will have their own perception of public opinion that translates to their audiences. One way in which journalists' views are communicated is through camera angles; for example, television systems generally use more close-up shots for candidates that they support (Noelle-Neumann, 1980).

One researcher who examined this relationship between the spiral of silence theory and the media is David J. Kennamer. Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann believes that, in general, journalists are much more liberal than the rest of the society. Using this assumption, Kennamer was able to determine that because of this undercurrent of liberal ideas, the content of the media is often liberal as well. This surrounds the population with a predominantly liberal society -- a society that the population solely depends on. Noelle-Neumann claims that this immersion in and dependence on the media has a very strong effect on individuals. It shapes their ideas and opinions, and makes them leery of expressing any opinion that may differ from these liberal opinions to which they are being exposed (Kennamer, 1992).

Once Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann's theory was presented in the mass communication field, many other people also began to examine it and to analyze the spiral of silence's credibility. Various tests and studies both supported and refuted her theory. Carroll Glynn did many tests in order to prove that the spiral of silence theory is valid. In one study, she and her colleagues examined the theory by using perceived voting outcomes and the actual behavior of the voters. Before the 1980 presidential election, Glynn conducted two telephone surveys with ninety-eight voters in Wisconsin. After the election, another interview was done in order to test the idea that people are more likely to speak their opinions if they believe they are in a majority. The data gathered from her research not only proved Glynn's hypothesis to be correct, but also showed that people will commonly claim to prefer one candidate when they believe that he will win the election (Glynn 1984). Glynn has since done various other studies to analyze the spiral of silence theory and people's expected support for their opinions and the expression of these opinions. In all of her studies, Glynn has been able to find a small but significant relationship between a person's belief that others share his opinion and his willingness to express that opinion. This is a classic example of the spiral of silence theory, and Glynn has been successful in discovering this relationship in all of the tests that she has done (Glynn, 1997).

Another researcher who has done several studies dealing with Noelle-Neumann and her theory is William Gozenbach. In one test, he experimented to see how the spiral of silence theory would work if it were applied to a controversial issue. From this study, he was able to determine that conformity is not only associated with dealings with other people and their opinions, but also with one's own psychological tendencies and social position (Gozenbach, 1992). In another study, Gozenbach analyzed the spiral of silence theory in relation to the question of children with AIDS being allowed to attend public schools. After his surveys and research on the topic, Gozenbach found that the people who thought that their opinion was the majority were the most likely to speak out. It did not matter if their opinion was actually the majority or not; if they believed it to be, then they would voice their opinion (Gozenbach 1994).

As more people performed tests on the spiral of silence theory, they began to find discrepencies. Hernando Gonzales was one person to find some problems with Noelle-Neumann's ideas. He did a study on whether the spiral of silence theory could be applied to a third world setting. The research that Gonzales used was based on the 1986 revolution of the Philippines. From his findings, it was evident that the mainstream media was not successful in obtaining public support for the discredited government, a goal that they should have been able to accomplish had the spiral of silence worked as Noelle-Neumann originally described. His research did find, however, that an alternative media was capable of swaying public opinion with its more diverse reporting methods, a finding that shows that the spiral of silence theory is not completely incorrect (Gonzales, 1988).

Cheryl Katz and Mark Baldassare conducted a study in order to discover whether people who know that their opinions are unpopular are still willing to speak out. After surveying voters in conservative Orange County over the telephone and asking the political views of each, they were able to disprove Noelle-Neumann's theory in this case. Katz and Baldassare asked each of their subjects if they would be willing to talk to a reporter about certain issues and allow their names to be printed along with their comments. Although the initial hypothesis, according to Noelle-Neumann at least, would be that the people with more liberal views would be less willing to talk because of a fear of isolation once their opinions were made known. In actuality, though, it was age, sex, and income that had more effect on a person's willingness to speak out, and people who held minority views were just as outspoken as the rest (Katz, 1992).

Daniel Lasorsa, however, argues with both these ideas and Noelle-Neumann's. He believes that it is circumstances such as political interest, self-efficacy, firmness of views, and the use of the media that determine a person's willingness to voice his opinions, and not merely education, income, gender, and age. Lasorsa feels that it is not the public as a whole that people fear isolation from, but rather specific groups. He also believes that people are more likely to be outspoken because of the positive influence of winning rather than the negative influence of fear of isolation that Noelle-Neumann emphasizes. He thinks that people are more likely to attempt to win acceptance into a group by speaking out, rather than remaining silent, because the feeling of winning is too great to overcome (Lasorsa, 1991).

The person who has the most controversial argument with Noelle-Neumann, however, along with the most resistance to her spiral of silence theory is Christopher Simpson. Simpson describes many problems that he finds with the spiral of silence theory and personally attacks Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann herself. He feels that her theory is biased and incorrect because of her history as a journalist in Germany during the Hitler era. He states that this causes her to display a distrust of diversity and plurality. He also thinks that her life in Nazi Germany caused her to have a contempt for democracy and the public, bringing her to find ways to use the liberal media as a scapegoat. Simpson contends that she too often uses her opinion as fact in order to prove her points (Simpson, 1996).

Simpson,s article, once it came into public view, brought a flood of argument. H.M. Kepplinger questioned Simpson's use of Noelle-Neumann's biography in the evaluation of a scientific work, finding problems with Simpson,s allegations about Noelle-Neumann,s past (Kepplinger, 1997). Noelle-Neumann herself also addressed Simpson and attempted to explain certain elements of her past. She described the horrible conditions that she was made to work under as a journalist under Hitler, explaining that although she was forced to write under certain requirements or face appalling consequences, she still preserved her beliefs as well as she possibly could and never had Nazi sympathies (Shea, 1997). She also alleges that, as is obvious in his misinformation and mistakes in detail, Simpson understands neither the spiral of silence theory nor the way the public functions in a dictatorship (Noelle-Neumann, 1997).

Although the spiral of silence theory has been tested, analyzed, agreed with, and argued against many times since Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann introduced it to the world of mass communications, it will continue to be poked and prodded for years to come. In some instances, minority views will indeed die out simply because no one is willing to express them. In other instances, however, nearly everyone will wish to speak his mind and let his voice be heard. The spiral of silence theory raises more than one good point and provides a compelling explanation of the workings of public opinion, but people's willingness to express themselves depends on far too many factors to be explained in one limited theory.

Bibliography:

Dreyer, E.C. and W.A. Rosenbaum. (1966) Political Aspirations and electoral behavior: Essays and studies. Wadsworth.

Glynn, Carol J., Andrew F. Hayes, and James Shanahan. (1997) "A meta-analysis of survey studies on the spiral of silence." Public Opinion Quarterly. Vol 61. Elsevier Science Publishing Company.

Glynn, Carroll J and Jack M. McLeod. (1984) "Public Opinion du jour: An examination of the spiral of silence." Public Opinion Quarterly. Vol. 48. Elsevier Science Publishing Company, Inc.

Gonzales, Hernando. (1988) "Mass media and the spiral of silence: The Philippines from Marcos to Aquino." Journal of Communication. Vol. 38. Oxford University Press.

Gozenbach, William J. and Robert L. Stephenson. (1994) "Children with AIDS attending public school: An analysis of the spiral of silence." Political Communicatin. Vol. 11. Taylor and Francis.

Gozenbach, William J. (1992) "The conformity hyothesis: Empirical considerations for the spiral of silence's first link." Journalism Quarterly. Vol. 69. The Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communications.

Katz, Cheryl and Mark Baldassare. (1992) "Using the "l-word" in public: A test of the spiral of silence in conservative Orange County." Public Opinion Quarterly. Vol. 56. Elsevier Science Publishing Company.

Kennamer, David J. (1992) Public Opinion, the Press, and Public Policy. Praeger Publishers.

Kepplinger, H. M. (1997) "Political Correctness and Academic Principles: A reply to Simpson." Journal of Communication. Vol. 47. Sage Periodical Press.

Lasorsa, Dominic L. (1991) "Political outspokenness: Factors working against the spiral of silence." Journalism Quarterly. Vol. 68. The Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communications.

Noelle-Neumann, Elisabeth. (1981) "Mass Media and Social Change in Developed Societies." Mass Media and Social Change. Sage Publications.

Noelle-Neumann, Elisabeth. (1980) The Spiral of Silence. The University of Chicago Press.

Noelle-Neumann, Elisabeth. (1997) Statement delivered at the ICA Conference, Montreal Saturday, May 24, 1997. Online: http://www.uni-mainz.de/~ifpwww/statement.html

Ross, Edward Alsworth. (1969) Social Control: A Survey of the Foundations of Order. The Press of Case Western Reserve University.

Rousseau, Jean Jacques. (1950) The Social Contract and Discourses. E. P. Dutton and Co., Inc.

Shamir, Jacob. (1992) "Information Cues and Indicators of the Climate of Opinion: The Spiral of Silence Theory in the Intifada." Communication Research. Vol. 22. Sage Periodicals Press.

Shea, Christopher. (1997) Protocol of the telephone interview by Christopher Shea, Chronicle of Higher Education, with Professor Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann, Institut fur Demoskopie Allensbach. Online: http://www.uni-mainz.de/~ifpwww/protocol.html

Simpson, Christopher. (1996) "Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann's "Spiral of Silence" and the Historical Context of Communication Theory." Journal of Communication. Vol. 46. Sage Periodical Press.

Taylor, D. Garth. (1982) "Pluralistic ignorance and the spiral of silence: A formal analysis." Public Opinion Quarterly. Vol. 46. Elsevier Science Publishing Company, Inc.

- If you had to make the decision, would you say that the Federal Republic should recognize the DDR (East Germany) as a second German state, or should the Federal Republic not recognize it?

This page design copyright 1999 by Steve N. Jackson.

Contents copyright 1999 by Jill Martin, Karin Peters, and Steve N. Jackson

Version 7.09 (19 July).